- Home

- Tatiana Ryckman

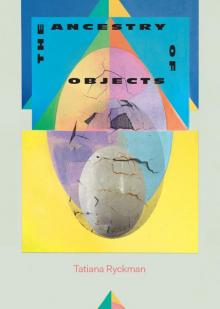

The Ancestry of Objects

The Ancestry of Objects Read online

PRAISE FOR The Ancestry of Objects

“Ryckman writes with cool, tightly packed precision on the futile ways people try to fill the emptiness and absence of life with objects and religion and desperate acts … A hypnotizing, bleak account of the ways people trap themselves in their own minds.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Ryckman’s The Ancestry of Objects accomplishes a difficult and compelling tension with lyrical prose that ropes readers into a nuanced depiction of the pleasure and pain of human relationships. She renders the figures of her fragmented novel with a stark tenderness, reflecting the beauty and unattractiveness of desire. There are no villains, no heroes, just complications between people whose flaws will draw readers to recognize themselves and our shared yearning to be known.”

—Donald Quist, author of Harbors and For Other Ghosts

“I’ve always loved Ryckman’s fiction, but nothing in the idiosyncratic originality of her short stories prepared me for her stunning novel with its dark eroticism, its plunge into depths of loneliness, and its quest for paradoxical liberation. Her extraordinary narrator lives in a state of erasure but thinks as plural: the social self for whom everything is always “fine”; the guilty, sinful self as defined by the now-dead grandparents; the self who needs to be seen through the outside eye of the absent lover, the absent God; and most of all, the self who feels dead in daily life and alive when courting an exuberant annihilation. In reading this powerful and disturbing short novel, I found myself splitting as well, into the reader who could not put these pages down, and the reader who had to, in order to regain her equilibrium and catch her throttled breath.”

—Diane Lefer, award-winning author of California Transit, playwright, and activist

PRAISE FOR I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do)

“(Ryckman) has joined the likes of Clarice Lispector, Claudia Rankine, and John Berger.”

—Matthew Dickman, author of Mayakovsky’s Revolver

“Ryckman’s reflective novella unfolds in 100 tiny, often forlorn chapters, each micro-numbered (from 0.1 to 10.0) and given a page of its own. Through this, form and content merge, as the narrator attempts to absorb the lessons of a failed long-distance relationship and, in turn, understand herself … The isolation of each individual entry underscores this haunting story from beginning to end.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Keenly felt and fiercely written. Tatiana Ryckman is a revelation.”

—Jennifer duBois, author of Cartwheel

“Ryckman has written the anti-love story within all of us. A book so earnest and sharp in its examination of heartbreak, it will make you ache for all the people you haven’t even loved yet.”

—T Kira Madden, author of Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls

“Tatiana Ryckman has written a wonder; a remarkably accomplished work of such keen observation and emotional complexity as to rival those texts—Maggie Nelson’s Bluets come to mind—with which it shares some literary DNA. Ryckman is a ruthless investigator of reckless desire … I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do) asks—newly, stunningly, with precise prose chiseled from stone—what it is we’re meant to do when the source of our appetite is beyond the realm of our own cognition, and following this narrator in pursuit of the unanswerable is a reading experience as gutting as it is thrilling. One finishes this book with the simple thought: Now here is a person.”

—Vincent Scarpa

THE ANCESTRY OF OBJECTS

Tatiana Ryckman

DEEP VELLUM PUBLISHING

DALLAS, TEXAS

Deep Vellum Publishing

3000 Commerce St., Dallas,Texas 75226

deepvellum.org · @deepvellum

Deep Vellum is a 501c3 nonprofit literary arts organization founded in 2013 with the mission to bring the world into conversation through literature.

Copyright © 2020 by Tatiana Ryckman

FIRST EDITION, 2020

All rights reserved.

Support for this publication has been provided in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Texas Commission on the Arts, the City of Dallas Office of Arts and Culture’s ArtsActivate program, and the Moody Fund for the Arts:

ISBNs: 978-1-64605-025-3 (paperback) | 978-1-64605-026-0 (ebook)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Ryckman, Tatiana, author.

Title: The ancestry of objects / Tatiana Ryckman.

Description: First edition. | Dallas, Texas : Deep Vellum Publishing, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020010104 (print) | LCCN 2020010105 (ebook) | ISBN 9781646050253 (paperback) | ISBN 9781646050260 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Psychological fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3618.Y353 A69 2020 (print) | LCC PS3618.Y353 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020010104

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020010105

Cover Artwork and Design © 2019 Sonnenzimmer

Interior Layout and Typesetting by Kirby Gann

Text set in Bembo, a typeface modeled on typefaces cut by Francesco Griffo for Aldo Manuzio’s printing of De Aetna in 1495 in Venice.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am forever indebted to Yaddo for the time and space to write, and to the many readers whose guidance and encouragement made this work possible: Boomer Pinches, T Kira Madden, Ian Patrick Miller, Lisa Wells, Charlie Clements, Rob Reynolds, Levis Keltner, Caitlyn Renee Miller, Jen Maidenberg, and Emily Roberts. I am grateful to Nick and Nadine of Sonnenzimmer for their amazing work on the cover, and to my publisher, Will Evans, whose patience and insistence brought this manuscript to life. Finally, I could never have written this book without Ed and Jennie and the house that they built.

The premeditation of death is the premeditation of liberty; he who has learned to die has unlearned to serve.

—Michel de Montaigne

PROLOGUE

When he pushes us over the kitchen sink and lifts our dress, we watch the fading sun glint off the faucet. On the first strike, waves move through our skin and he pulls his hand back; we hear the hollow crack before we feel the sting. We anticipate the second slap and brace ourself with whitening knuckles. A ceramic finch watches, detached. The edge of the sink is smooth but unforgiving where it digs into our ribs just below our breasts. We think Tits; we command him to Feel my tits, but we don’t know where the words come from or go.

The first waterfall of moisture runs down our thigh with the sweat. It splits into two streams at the knee. His fingers wear the memory of her hair, and the sweat of our lower back mixes with the salt of her tears and the salt of his come landing like a flock of birds on our back. He smooths the cream over our spine like icing. He licks and puts his hand to our mouth to taste.

The glaze of his fingers fills the air in front of our face with the scent of warm dough.

Her tears and hair and our sweat and his come scrape onto our teeth, and we taste the hollow sound of each slap echoing through the porn of our memory. He relaxes his hand in our mouth until we let go. His lips touch down on our back in the erratic pattern of ejaculate. He rubs the come in like lotion and it dries into a tight flaky skin that peels like a sunburn.

He walks through the space he’s claimed and sits. The chair rolls a few inches just as it used to every time our grandmother fell into it and slid across the kitchen t

ile before bumping into the table, shuffling papers and silverware into stacks.

As we move toward him we don’t think about what we’ve done; we think instead about this man: the clean crease pressed into his pants, the good shape he’s in, considering, about how easily he manufactures a smile, a history, money. Our own history has been reduced to the last few moments of our mutual existence, of his silent panic, and the wife’s starved fingers as they wander the sparse forest of his straight chest hair. We think the phrase Snake in the grass. Think Babes in the Wood. Think Hansel and Gretel and their trail of bread. Think of the trails left by the wife’s tears when the man says first I love you, and then, But—

When we imagine him leaving her, he is already mistaking her hair for ours and does not notice the black makeup on his lips when he kisses her closed eyes goodbye.

When the man wipes her tears away, his fingers claim he is sensitive. And she whispers But—

and then,

I love you.

And they do not hear the things they are not saying.

His long fingers will work around the familiar shape of her, and she will think this means he is changing his mind. That he’ll stay. And when, for a moment, it seems he might cry, she’ll believe he is repenting.

But he will be saying goodbye.

We lean against the counter and leak onto the linoleum floor. We think of the stain he’s made in the house, in us, and wait for the moment when he will leave and we can toy with the lonely wetness of our cunt and the house, the whole house holding us in a warm echo. We will come fondling the bruises he’s left.

THE ANCESTRY OF OBJECTS

We learn the man:

When he comes in with a bag, he wants to stay the night. When he cooks at our stove, we pour another glass of wine. We rub the dry fabric of his shirtback lightly until the prints burn off our fingertips. We grip loosely the knob of his elbow and he tells us the history of the day. A good day. Twenty dollars in an old coat pocket, a client pleased, a baffling sum of money that is easier understood as an example of how little we know—about his day, about his fingers when they are not wrapping themselves around our throat, about the desert that lies between us—than of his own work done well.

He finishes his story with a smile and: It was good—Now it’s good. He moves his mouth to ours and sets down the old spatula, plastic handle disfigured with heat. He slides his hand from our hip to the soft flesh of our ass and pulls us to him. He says he can be very generous and we resent instantly the implication that we have been bought. That we are indentured. That anything that is ours to give is owed or perhaps already owned by the man. He radiates a salesman’s thin integrity. We enjoy the tottering infant of hate we’ve conceived for him and cultivate it, so we laugh, we pretend that he’s said nothing. We take his hand and examine the roadmap of his palm. We joke: This long one must be money, maybe the shorter one is life.

We are thankful for the distraction of water boiling over, spilling white foam across the oven top.

And the first time:

We meet the man at the expensive bar while privately celebrating the end of our life.

The toaster we will throw in the bath.

The car that might run too long in the garage.

The many pills that remain from those who have gone before us.

After “we” and “regret” and “to inform you,” the words mean nothing: Streamline, technological advancement, efficiency. We are replaceable, so we will be replaced. Our life, so long unnoticed even by us, suddenly accelerating toward an inevitable end. We can come in, the letter says, to pick up our final paycheck. Otherwise, it will be mailed.

To be free of the daily commute, of the way people arrange themselves at lunch at a distance from us, of the news overheard rather than delivered—to be free of these unencounters would be a solution to the problem of our limited existence if there were something to take its place. The way the other women whispered their secret futures in anticipation of this end: A father who needs to be cared for. A sister who’s been asking her to move closer to home. A job that’s already been interviewed for.

But we’ve learned already that our freedom is a more difficult cage to escape than oppression.

On the first day after we receive the letter, after pressing the crescent shape of our nails into the soft skin of our biceps, we model the fantasies of the end of our job and house/home on the end of times our grandparents warned of in lectures we did not listen to. They begin with the appearance of The Beast and then the flight to the caves, and finally, for us, the third or fourth or millionth advent of nothing. A holy final void.

The new meaninglessness of days makes the hours roll out like cruel waves, languid and unconcerned. We are panicked by the disappearance of obligations that had for so long sufficed for purpose. And beyond the duress, admonishment for it. What right do we have to our inconsolableness? The house is inherited, paid for. We could live for a few months, if we could live under the unbearable crush of time. We are not destitute, just precarious. Concerned not with how to lift ourself from the bottom of this pit, but how much farther still is the fall? What sort of future exists for someone who has become obsolete?

We mourn too the end of endless days filled with the delicate dictation of biological errors. We miss in advance the responsibility to witness the repeated failure of body after body described by the doctor; we meditate on the comforting weight of everyone’s fragile lives as narrated through headphones, the familiar cadence of a woman’s voice reading without emotion the tumors and fractures lit up from behind comma from within—the voice of quick and unremarkably slow deaths and injuries of strangers so ingrained in our mind that they seem to foretell our own slow death period Her calm voice the one we use to describe our frustrations with traffic in the street outside the window, the voice that narrates the news of the day. The woman’s voice, the invisible doctor’s voice, recites the brokenness of strangers as we digest our breakfast. It is the voice we use when we defend ourself against the drawl of ancient, well-meaning reproaches. Our grandparents’ easy unkindness composing the endless loop of our childhood mistake. The mistake of existing. And in the bathroom mirror, the emotionless voice of dictation is ours when we unscold ourself: We are notbad. We are notsinful.

Now, now, we say with bitterness for our training in self-flagellation. We wish again that they would die but remember, again, there’s no need. Everyone is already dead. Except for us.

At the bar the woman’s voice dictates the book we are reading in the poor illumination of mood lighting: And as I walked on comma I was lonely no longer period

When he sits at the bar, waiting for his table and his woman, we see from the corner of our eye that he will speak to us, and when he asks what we are reading we resent him for kicking the crutch of loneliness out from under us like the job, gone, and one day the house, gone, and soon, life, gone. Us, gone.

He has taken her out for dinner, and while she is in the bathroom he takes our time because he does not know it is ours. Because he is generous and believes his attention is a gift. Because perhaps he is afraid of moments alone. And he asks about the book as if we brought ourself for him. We lift it so he can read the title without our needing to speak. We imagine him mouthing the words, reading them like an analog clock. We don’t need evidence to water the seed of our malice.

We attempt to carry on despite the intrusion but manage only to reread Now comma don’t think my opinion on these matters is final comma he seemed to say comma just because I’m stronger and more of a man than you are period

First time? he asks and we shake our head no. As she crosses the floor of the restaurant on her return from the restroom he adds with unanticipated compassion: It’s funny, but I never expect him to die.

We look past the yellowed pages and see the delicate lines by his eyes make an estuary of sadness. His lips tighten into a resigned smile, subtle but controlled, and we believe in that moment that he could have cracked easily like

the thin bones in her wrists.

Me too, we think, maybe say aloud, without thinking, to the nothing that is listening. His face is a mask of politeness. We nod to acknowledge her, but she doesn’t see us, doesn’t need to see us because he is generous. She is wearing a new dress. They are shown to a table and float away on a cloud made of a life empty of complication. When we try to pay for our drinks, the tab has been taken care of, and we are ashamed. We are caught between needing generosity and dying in it. Between wading into the terrifying void that lies ahead and enjoying the excruciating final moments.

We think of the momentary unveiling of the man’s sadness.

And of the celebratory red of our own blood merging with water.

At night the house holds us like the thin shell around a yolk. We slide out of our shoes at the door. A small, dark enclosure crowded with sweaters and rain boots smelling of roses and mothballs leads to the kitchen, and we stop to notsee, notlisten, notthink about what is or is not in the house with us. Our persistent fear of intrusion butting against the persistent nothing that’s there, and our persistent feeling that it will always be nothing, that the loneliness will deafen us to joy, should such a feeling still be possible. We walk through the long, open rooms, past kitchen and dining room and finally in the soft cushion of afghans and eyeless stuffed animals no longer seen, we bend to run fingers through the thick weave of carpet. Plastic fibers catch our nails as we lower ourself onto its bed. We think Fur and Counting sheep, and of his woman’s forearm in an X-ray, tied at the wrist to the table so that when they order her favorite meal she can never quite reach. Can never taste it.

The Ancestry of Objects

The Ancestry of Objects