- Home

- Tatiana Ryckman

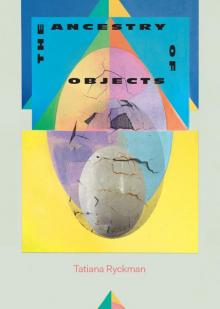

The Ancestry of Objects Page 5

The Ancestry of Objects Read online

Page 5

David does not ask again for our number. He comes and goes as he pleases.

Is there a word for finding pleasure in fear—would Lara say the strength of these feelings isn’t love, but terror?

And once on the playground when we corrected a classmate about the true day of the Sabbath, explaining to them only pagans worship on Sunday, we felt a smug superiority for our membership in the correct religion. And with the pride came enormous fear that no one else knew it was all a lie.

When David leaves we lie on the bed and move the tight muscles in our lips, tonguing the metallic dents left by our teeth. The first drop startles us, a confusing tap at the end of the bed. We see particles of moldy dirt splash on the tattered rug. We look up, a brown ring grows on the ceiling, and David becomes the hum of the refrigerator buried under everything, the single drop drowns our thoughts of him, we burn with helplessness at the intrusion.

Surely, we say in the calm voice of the woman, there is a logical solution period

Surely we have been negligent, our grandparents remind us of our Christian duty to cleanliness and Godliness. Surely we know better. Surely they raised us better than this.

When we place it under the leak, the pink plastic trash can makes a hollow tap with every drop. Each echo resounds of the bills that will collect. Even the flicker of gold on the foggy memory of David’s left hand is no longer a liberating, but now a fresh, suffocating end. The bulge of grief and the unstoppable progress of sadness that chokes us like David pressing into the back of our throat.

Backlit images of X-rays filter through the imagined lengths of rope we consider tying first to our neck and then the metal bar of the closet. The house weeps from the inside into the trash. Lightning lights the house like the beginning of the universe: the womb of our home fills with an artificial brightness, but lacks the strength to stop the mess of the outside coming in.

We curl into the nest of the bed, wrap the house around our cancer of sadness. Crying contorts our face into an ugliness that we cling to until the sobs and muscles moving involuntarily disgust us. Gasps first caught in our throat drown in the salty swamp of the pillow until, nestled in our own shallow cave of pain, we fall asleep exhausted, without David or thoughts of David or even the desire to be consoled.

Who can lift the burden of sadness from us? Not David. Nor can we take David’s. No matter how great our capacity for pain, we cannot carry his, like a cumbersome parcel, dutifully to the grave—the only future we trust. Though we understand death is only an easy solution for the already dead, we can’t imagine how else one elegantly exits the unbearable reality of the present moment.

We develop a desire: escape. We want to fall through the trap door of our life to something else—something that will be better because it is different. Though we see David’s flaccid arms, we want him to catch us when we come out on the other side. No—we correct ourself—we want him to want to despite his inability.

Around the tub is a clutter of half-used shampoo bottles a decade old, Old Spice, bubble bath, crackled slivers of soap dried to their dishes. We put it all out of focus. To our blurred vision there is nothing as far as the eye can see.

We drag the razor across our arm without pressure, just an apathetic curiosity. Pale hairs yield to the blade. We run it along our stomach, our hands, our face. Places that once appeared hairless grow a dull bald sheen. This is our body, we say to ourself. The body is a temple. A temple is a house of God. God is a construct, we counter, invented to explain earth sciences and pacify the existential torment of the human experience.

And yet we feel no better.

Sometimes I’m sad, we admit to him one night in comforting lamplight during a visit when we are still new/don’t say: every day I want to die. And he puts his arm around us. This is what the man can do; this is all he can do.

Are we dishonest because we are embarrassed, or because we do not believe he will care? Should he?

Don’t ask questions, for God requires us to have faith like a child. Don’t touch, for your body is a temple. Don’t be that way, who will want you? Be good. Be a good girl.

When David whispers That’s a good girl, ride my cock like a good little slut, we do as we always have and obey.

David never calls at midnight to say:

There are no numbers to call and no distant voices traveling detached from our bodies and nothing outside of us can say I miss you. or How are you? or I’m thinking of you./Are you touching yourself? And we do not say aloud to ourself that this will make it easier later, when it is over, so we will not be tied to the man by phone lines, we will not know the manicured lawn in front of his house, the proximity to favorite restaurants, the benign good taste of his life; it is good to keep him out of reach. And David does not say it will make it easier to keep from his wife when she returns, though it will, and he does not invite us into the clean luxury of his existence. Instead, David appears on the cement step on the seventh day of Lara’s trip, like a private Sabbath, holding a paper bag. I brought some things for dinner, he says walking in. Have you eaten already?

No, we say, confused by the comfort of pretending like children to be man and woman. When he begins to fill the dented pots with water and turns the gas on under them, we know to rub with our fingertips on the dry fabric of his shirt as he says it’s a good day: the twenty dollars in a pocket and work and now he’s here and he says that we make a good day. And our day, our existence as it crumbles around us is painted over in more pretending: that we should fill his glass; we should read the lines of his palm with humor and good fortune; we laugh when he says, I can be generous, as if: I can make you/this easy. We do not correct him that it is us who is giving so freely what he is looking for. That he will never be generous with what we need. We don’t want to be saved, just seen, to be real, okay, enough, but the water boils over, the white foam spill distracts him so that when he lifts the lid and steam fogs the clock and small window that looks out to the front door, we breathe deeply to forget as if it is the same as forgiveness, and when he replaces the lid he begins to pull new items from the paper bag: oil, spices—and we imagine these things lining the shelves in the clean hush of a remodeled kitchen, we imagine Lara by the stove, a good wife at the stove—and we say, I have all of these things. Laughing that he thinks we do not live in this house, or that we exist from nothing, but when we remember the wilted produce in the crisper drawer and the blank stare of the shelves every afternoon as we try to sustain or distract ourself, we wonder if he is right, if we do not know ourself at all. If we have never been seen because we aren’t here.

I didn’t want to make any assumptions, he says offhandedly, running a hand down our back, and we shiver under the touch. We pull a thread of pasta from the pot and throw it against the wall for the first time since childhood, and it sticks in the shape of a cursive S. He removes the pot from the heat, and with its steam rising from the sink where he has drained the water, he holds us. The lip of the sink pressing into our low back, a cooked smell surrounds us like a shower and we cannot distinguish his body pressing against us from the house he presses us against. And after dinner, on the couch he says again: I didn’t expect this. We wonder again what This is, but smile instead, running our fingers down his long thigh until the friction on our fingertips feels like a burn.

Why us? we want to ask, but say instead: Have you ever broken a bone?

Of course, he laughs and extends the fingers of his left hand. There is an unusual twist to the index finger so that it appears to be permanently pointing to the right.

What happened? we ask, taking the hand in our own to examine it more closely as if we might see under the skin and hear the doctor’s voice describe the broken parts of David aloud so we don’t have to pull them from him.

Oh, it got smashed with a baseball bat.

You played baseball?

No—he seems reluctant to continue—well I did, in elementary. T-ball, he says and laughs.

But that’s not when yo

u broke it?

No.

We watch the tightening of his jaw, and the lines at the corners of his eyes deepen as he knits his brow. It is a restrained expression, like puzzling at a difficult math problem to avoid the smart of admitting you don’t know. I didn’t smash it, he says finally. My dad did. It was an accident, but he was angry, and he was often angry, so it’s always been hard to be sure. His face relaxes. It’s complicated, he says dismissively.

No, we say, it’s not. It’s just hard.

Later, he presses our face into the mattress and we stand on our toes to meet his hips. And while we fill with a metallic dread, we don’t imagine that in the inevitable, excruciating end, he will stay. He is hers. Behind us he is a figure lost in the corners of our eyes, a man already disappearing even when we are closest. He presses the back of our head, our breath catches in the folds of old blankets, he pulls our hair so the breath is squeezed out in thin cords of a neck stretched taut. And through clenched teeth: You like that. And we remember that now we are his, so we like it. We remember we can be generous and give readily so that nothing can be taken from us. But we say only Oh, God.

The red sweater is matted from the rain. Someone has hung it over an informational plaque describing native plants. We imagine their reluctance to touch it. Someone else’s clothing, so personal, and left to be sullied by the weather for an indeterminate length of time. Has the owner of the sweater been back since the time of their loss? Have they also seen it and been too ashamed to take it home? Were they an out-of-town guest, on a walk with their sister, and now are they home catching a chill and wondering about their sweater? Are they thinking about it right now? Can they see it through our eyes? If we think of each other at the same time, are we connected even if we can’t be together?

On the way home we go by the cemetery. We visit the plots of our grandparents that once looked like twin beds of unestablished sod against the endless carpet of green. We still can’t quite believe that they’ve moved. That their bodies are not shuffling through the long house, but are here, awaiting resurrection. In this politely manicured expanse they seem at a loss for words. Perhaps it is a sense of propriety that keeps them from expressing indignation, resting, as they are, in the Lord’s waiting room. Or maybe it is a fear of appearing unfit for entrance into the Heavenly Kingdom. Or maybe it is we who require all of their earthly possessions to animate their ire, like the tools of a well-cast spell.

Each evening Lara is away, David comes earlier and leaves later each morning so that the days with him grow longer, the very small hours of night an ocean wide forever so we can take more of him into ourself before she is back and David tells her, we see so clearly in our mind the way he will say, kissing her eyelids: I love you. Then: But—and his hands in her hair and the weight of her, the baby body weight of her head resting in his hands, as easy to crush. And he walks out to this, another life. Even if we chant each night that we are some temporary other existence—Lara surely knows why people behave this way, has read many books on the subject, and she knows why people leave to see what else—we can still see him arriving in our life like a ship. We can so easily mistake his persistence or desperate reaching for devotion.

Lara, with all her knowledge and training, could give a lesson on what is wrong with the man, and with us, and prescribe a pill or routine. And her? Why does she stay?

•

And what object lesson do we give with our presence in the man’s life, in Lara’s life without her knowing? Just the objects themselves, the miscellaneous articles in drawers and shelves stacked and corners meticulously filled with all the treasures piled and forgotten. We could teach the ancestry of objects preserved as a museum to the absence of love, to tenderness stored more faithfully in hairpins collected in mason jars than in our lineage of fallible hearts.

In the morning he dresses for work and we watch from the mess of floral sheets as he tells us about the appointments for the day and the way a coworker reminds him of a friend from graduate school and how he is always stopping himself from being overly casual with her, since she seems so familiar. We smile at the story and watch as a wave of suspicion crests in our mind. We remember the job’s quick ending, the parents’ absence, how easy it is to find a solution to the problem of us. That we are replaceable, so we will be replaced.

Roses on a yellow background interrupt our limbs as they stick out of the bed. When we reach for him, he comes back smiling. For this moment—when he is still buttoning his shirt and looking down at the button with his mouth in a frown like a child working out the mechanics of a jacket—we reach out and he comes, and though we know he will leave, for the moment he is here and his presence is a quiet affirmation that we, too, exist.

Were we always alone?

There were schoolmates and sleepovers, but even in these memories it is the ear of an invisible friend we whispered our secrets to. Grandfather reading quietly in his chair, grandmother at the stove or by quilts well-intended and always half-finished. Sometimes visitors sat with the grandparents at the table and talked quietly, endlessly.

Kids would say Your parents are so old. And we would clarify, Grandparents. And they would ask, Why do you live with your grandparents? And we would say Because my parents are dead, and find pleasure in their uneasy apologies and slow backing away.

It was the eyeless fake dog perched on our dresser we fell in love with first, then blankets, and hat pins and vases, rusted simple machines in the garage, and the smarting of a rubber band against our wrist. And later, clippings of celebrities from magazines who might understand us based on certain melancholy expressions, and later still, whole characters from books and the color and smell of the paper where they lived, and the moments we spent together, and finally, nothing. Just a bland hunger that persists no matter what we feed it.

When the notice comes from the city, we open the garage and climb through the spiders to remove the push mower. Even in our youth when we resented the obligation, we appreciated its simple design and straightforward mechanics. As we wheel it into the sun, we see the blades are rusted and fantasize the catch of skin on rusted metal. Tetanus. Dismemberment. This is as far as our imagination will take us. We push the machine across the cracked driveway to the lawn and begin. It is more difficult than we remember. We strain up the slope and allow the heavy blades to pull us when we turn to go back down. Though it is forbidden by the grandfather who comes out to check our work, we change directions and pull along the side of the slope creating an inconsistent pattern in the uneven grass. He tells us to oil the machine, to sharpen the blades, to maintain. We push across the hill. The damp grass sticks to our shoes. Our hair, stomach, back, groin, legs are wet with sweat. Neighbors we don’t know say hello. We nod in reply. There is pleasure in the strain. We know our back will hurt. We know we will lie in a cold bath with a beer. We know we will be reminded of the effort tomorrow and are reminded of David and marvel that we have not thought of him until now.

As we sweat and push, we think of the pastor telling a joke:

What was Boaz before he married?

Ruthless.

We see still the vision of our grandparents contracting bitterly in on themselves and how we formed the word in our mouth: Ruthless. And whispered it to ourself all that night like an incantation.

Moments with David are episodic and, because we do not know each other, seem to float without context:

What did you do with all your time before you came here? we ask, naked in bed beside David’s body. He laughs the way he laughs when he is uncomfortable. He laughs often.

I guess I went home. I don’t know what I did there—eat, sleep. Read sometimes, but not as much as I used to. Talk to Lara.

Who knows what happens in the liminal hours? we say, as if it were a joke.

What did you do before me? he asks with unusual interest.

What do you do is simply: How full is your life? Mine is empty, will you fill it?

And so what do we say with our ow

n enthusiasm for the man? Make me in your image, make me wealthy, comfortable, secure. Make me someone with someone.

•

We do not say: pluck the hair from our legs one at a time. Nor: practice drawing exact circles with the nubs of empty pens, bite every piece of fruit in the dish and leave the rest to rot, stare at the shelves of the refrigerator and feel a quiet vibration in its eerie light, lick the sharp new hairs that grow back after we’ve cut them off our arms, braid the short shag of the polyester carpet, hold our breath in the tub, or walk to the cemetery down the road to lie on our grandparents’ graves. The only place where they’re quiet.

I like to read, too, we say. I’ve started walking to the park.

We do not tell him about the sweater, and the withholding makes it ours.

The rough grating of synthetic fibers under us as David pushes us down burns away skin and the vestiges of our isolated history. That once: between the innocence of our carpet-bound adolescent despondency and David’s blind destruction of our memories of that time was the burn of a short brown carpet against our back and the blue flicker of a movie on the boy’s turned face. A few rooms away his parents sleeping, and a few blocks away the window to our room propped open, and after just a few moments his quiet pulling away and only: This was a mistake. Under David, we stare at the stippled texture of the ceiling and swallow our shameful need. That pitiful and persistent desire not to be a mistake.

The Ancestry of Objects

The Ancestry of Objects